Author: Cassio S. Namur. Lawyer, partner of Tortoro, Madureira & Ragazzi Advogados.

Introduction

A recurrent theme around the world, the international abduction of children, usually committed by their parents, does not escape the supervision of Brazilian authorities.

Brazil has a broad legislative system that aims to protect children and adolescents. Proof of this can be found in the Federal Constitution, which, in its “Chapter VII – The Family, the Child, the Adolescent, the Young and the Elderly”, in its article 227, establishes the following

“Art. 227 It is the duty of the family, society, and the State to ensure to the child and youth, with absolute priority the right to life, health, food, education, leisure, professionalization, culture, dignity, respect, freedom, and family and community life, in addition to placing them safe from all forms of neglect, discrimination, exploitation, violence, cruelty, and oppression. “

According to the Federal Constitution, the care of children and young people is a duty that falls on everyone, not just the family, including the State and other citizens, who must ensure that their rights are observed, as well as the provisions of custody and other related prerogatives.

At this point it is worth remembering the existence of excellent legal mechanisms in Brazil to protect the public referred to in this article. In particular, I would like to highlight the Statute of the Child and Adolescent, Law n° 8.069, of 07/13/1990 (“ECA”), updated over the years, one of the most complete in the world. Having as a parameter the constitutional guidelines, the ECA established norms with this intention in its articles 3 and 4:

” Art. 3 Children and adolescents enjoy all the fundamental rights inherent to the human person, without prejudice to the full protection referred to in this Law, being assured, by law or by other means, all opportunities and facilities in order to enable their physical, mental, moral, spiritual, and social development, in conditions of freedom and dignity.

Sole paragraph. The rights set forth in this Law apply to all children and adolescents, without discrimination based on birth, family situation, age, sex, race, ethnicity or color, religion or belief, disability, personal development and learning condition, economic condition, environment social status, region and place of residence or any other condition that differentiates people, families or the community in which they live.”

“Art. It is the duty of the family, the community, society in general and the public authorities to ensure, with absolute priority, the realization of the rights to life, health, food, education, sports, leisure, professionalization, culture, dignity, respect, freedom and family and community life. health, food, education, sports, leisure, professionalization, culture, dignity, respect, freedom, and family and community life.

Sole paragraph. The priority guarantee comprises:

a) the primacy of receiving protection and help under any circumstances;

b) precedence of care in public services or services of public relevance;

c) preference in the formulation and execution of public social policies;

d) privileged allocation of public resources in areas related to the protection of children and youth. “

Given this scenario, it is possible to conclude – from a legal standpoint – that the national rules are complete, comprehensive, and consistent with the country’s reality, and confirm the constitutional principle of the best interests of children and adolescents.

In this sense, the legal provisions mentioned in the Statute are intended to reproduce not only the Federal Constitution, but also what is provided for in the Declaration of Principles of the International Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations, on 11/20 /1989, ratified by Brazil on 01/26/1990, through Legislative Decree No. 28, of 09/14/1990, later promulgated by Presidential Decree No. 99,710, of 11/21/1990 (“Convention on Rights of child”). “Preceding the adoption of that Convention by more than a year, the 1988 Constitution was already in effect. It dedicates to children and adolescents one of the most expressive texts consecrating the fundamental rights of the human person, whose content was made explicit by the Statute of the Child and Adolescent, instituted by the aforementioned Law 8.069/1990”, as stated by José Affonso da Silva.1 All this compilation that I recall here already evidences Brazil’s concern in trying to meet the interests of the vulnerable in question.

But this is a brief introduction to get to the theme mentioned in the title: international child abduction.

1. International child and adolescent abduction in Brazil

According to the Hague Convention #28, of 10/25/1980, on Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, in force abroad since 12/01/1983 (“Convention”), the concept of international child abduction is defined as the wrongful transfer or retention in a country other than that in which the child was habitually resident, without the consent of one of the parents, legal guardians, or judicial authorization.

Brazil ratified the Convention many years after its creation. The National Congress approved it through the Legislative Decree n. 79, of 09/15/1999, and the Brazilian government deposited the instrument of adhesion to the Convention on 10/19/1999, and it became effective in the country on 01/01/2000, as verified by the Presidential Decree of Promulgation n. 3.413, of 14/04/2000, published in the Diário Oficial of the 17th of the same month.

The aforementioned Convention covers children and adolescents, since in its article 4 it provides protection for children up to the age of 16, ceasing to apply when the child reaches that age. It is worth remembering that the Brazilian legal description establishes as children, citizens with up to 12 years of age and adolescents those who are between 12 and 18 years old, as provided in art. 2 of the ECA, which states:

“Art. 2 A child, for the purposes of this Law, is considered to be a person up to twelve years of age incomplete, and an adolescent is considered to be one between twelve and eighteen years of age. “

I emphasize that from this excerpt on, I will use the term “child” to refer to both.

The two main objectives of the Hague agreement are defined in its Article 1, which reads as follows:

“Article 1

The purpose of this Convention is:

(a) to ensure the prompt return of children wrongfully removed to or wrongfully retained in any Contracting State;

(b) to enforce effectively in other Contracting States the rights of custody and visitation existing in a Contracting State.”

It is clear, therefore, that the Convention aims to ensure the prompt return of vulnerable persons unlawfully transferred to or wrongfully retained in any Contracting States of the Convention, and also to enforce guardianship and visiting rights between Contracting States.

To resolve this dramatic situation and request the return of the child to his or her habitual residence or correct a case of withholding, it is necessary that the event occurred less than 1 year ago (Article 12 of the Convention). Article 12 states:

“Article 12

“Where a child has been wrongfully transferred or retained pursuant to Article 3 and a period of less than 1 year has elapsed between the date of the wrongful transfer or retention and the date of the commencement of proceedings before the judicial or administrative authority of the Contracting State where the child is located, the respective authority shall order the immediate return of the child.

The respective judicial or administrative authority, even after the expiration of the 1-year period referred to in the preceding paragraph, shall order the return of the child, unless it is proven that the child has already integrated into his or her new environment.

Where the judicial or administrative authority of the requested State has reason to believe that the child has been taken to another State, it may suspend the proceedings or reject the application for the return of the child.”

For information, I occasionally receive inquiries from parents seeking news about their “abducted” children after this one-year period, which unfortunately means that the Convention can no longer be invoked and enforced. In these cases, parents will have to resort to agreements or go to court, through ordinary channels, in order to assert their rights and those of their offspring.

Restitution must be immediate, and the judicial or administrative authorities must take a decision within 6 weeks of the date the application was filed, as provided in Article 11 of the Convention:

“Article 11

The judicial or administrative authorities of the Contracting States should take urgent measures with a view to the return of the child.

If the judicial or administrative authority concerned has not taken a decision within 6 weeks from the date on which the application was brought before it, the applicant or the Central Authority of the requested State may, on its own initiative or at the request of the Central Authority of the requesting State, seek a statement as to the reasons for the delay. If it is the Central Authority of the requested State that receives the reply, that authority shall forward it to the Central Authority of the requesting State or, if appropriate, to the requester himself.”

The stipulation in Article 11 of the Convention means that it is a settlement without delay, as provided for in Article 12 of the Convention. If this deadline is exceeded, which is recurrent, the Central Authority needs to justify the reasons for the delay.

There are numerous reasons for international child abduction, such as domestic, physical, psychological or sexual violence. Or even situations of war or armed conflict, and lately even acts of terrorism can be considered as justification in certain situations. However, in a considerable number of cases, parents or legal guardians no longer reach a consensus about living together with their spouse or partner. And that type of situation ends up making it impossible for both parties to live with their children as a form of retaliation or even revenge. In this regard, it is important to mention that article 13 b) of the Convention, which stipulates the legal exceptions on the return of the child. Its interpretation, however, can generate several doubts, since meeting these objections means transferring, in many cases, the judgment of the divergence between the parents or guardians of the child to the jurisdiction to which the child was abducted, when all this discussion should be proven in the jurisdiction of their habitual residence. Article 13 b) thus provides:

“Article 13

Notwithstanding the provisions contained in the preceding Article, the judicial or administrative authority of the requested State shall not be obliged to order the return of the child if the person, institution or body opposing his or her return proves it:

a) …..

(b) that there is a grave risk that the child, upon return, will be subjected to physical or psychological harm or otherwise placed in an intolerable situation.

The judicial or administrative authority may also refuse to order the return of the child if it finds that the child opposes it and that the child has reached an age and degree of maturity such that it is appropriate to take his or her views on the matter into consideration.

In assessing the circumstances referred to in this Article, the judicial or administrative authorities shall take into account information concerning the child’s social situation provided by the Central Authority or any other competent authority of the State of habitual residence of the child.”

Therefore, it is necessary to reinforce that one cannot generalize or make the legal exceptions more flexible, nor disrespect the visitation rights of the parents or those who have custody or parental power. In this respect, Jacob Dolinger, when discussing the subject, states: “In the

appreciation of a phenomenon of the child itself by the parent, or sometimes by a guardian, the central problem is to determine the priority between the benefit of the child and the strict compliance with what has already been judicially established. If the primary concern is the welfare of the child, in many cases of abduction we should leave the child where he is, provided he is found to be doing well with the abducting parent in the new place and environment in which he is now. However, the solution would be different if we had to rigorously observe the fulfillment of what was judicially decided in the jurisdiction in which the child had his habitual residence, not condoning with frauds to the law and disrespect to judicial determinations, because if these are not respected we will be allowing that the parties take justice into their own hands and, ultimately, that children become pawns in their parents’ post-separation war, provoked by frustrations, bitterness and vindictive impulses.”2

Here it is important to highlight the seriousness of preventing the child’s contact with one of the parents or guardians and to guarantee at least the right to this contact, not to use the expression “visitation”. Many parents or guardians do this, perhaps unaware of the consequences that such action can cause their children or children in their care. To remove them from their home, social and school surroundings is a very extreme and harmful decision. And there can be no complacent attitude toward that choice. The possible or imminent rupture of the conjugality of his parents or legal guardians cannot also mean for the child the “rupture of the bonds between him and his parents. The minor must be treated as a person in development, a subject of law and not an object in negotiation. After all, the family is the axis of personal and affective fulfillment of its members, and it is here that the subject is formed and structured

psychically, in short, humanizes himself”, as Rodrigo da Cunha Pereira teaches us.3 In the same sense, I note the statement by Luiz Edson Fachin: “in the relationship between parents and children, the legal system must be inspired by values that foster a healthy and balanced family environment. The new Civil Code, in force since January 2003, when dealing with family power, welcomes this line of thinking, although it could have gone further in the sense of always recognizing the best interests of the child as the central core of the legal system’s concerns. The basis of these ideas is that the one who educates, in a dialogical procedure also renews himself, reinventing ideals and values”.4

It is common sense that children live with their parents or guardians as necessary for the better formation of the personality of adults, as this living together is in their best interest, of course with exceptions in cases where cohabitation is impossible in such a way that it harms the development of the vulnerable. For this, the Convention is an effective vehicle among adhering countries. Article 6 of the regulation states that each Contracting State shall designate a Central Authority responsible for the enforcement of the obligations set forth in the Hague regulation, which shall take all necessary measures to return the child as soon as possible to the country of his or her original residence or to establish rights of access that have been abruptly violated. Article 6 stipulates:

“Article 6

Each Contracting State shall designate a Central Authority responsible for carrying out its obligations under this Convention.

Federal States, States in which several legal systems apply, or States in which autonomous territorial organizations exist, shall be free to designate more than one Central Authority and to specify the territorial extent of the powers of each. The State making use of this possibility shall designate the Central Authority to which requests may be addressed for the purpose of transmission to the Central Authority internally competent in that State.

To make this possible, there is the Central Authority, which is a national internal body responsible for legal cooperation with other states and foreign organizations. It receives, analyzes, adapts, transmits, and follows up on requests for international collaboration, and represents the requesting state – including judicially – if the requirements for this are proven. It is certain, however, that the final decision lies with the Natural Judge, the Court where that child habitually resides.

In Brazil, the processing of cases of child abduction or re-establishment of custody or visitation rights, under the scope of the Convention, is currently the responsibility of the Federal Central Administrative Authority for International Adoption and Abduction of Children and Adolescents (“ACAF”). It is an agency linked to the Ministry of Justice and Public Safety, through the National Secretariat of Justice and under the management of the Department of Asset Recovery and International Legal Cooperation. When these processes are judicialized, it will be the Office of the General Counsel for the Federal Government (“AGU”) that will represent the interests of the foreign state requesting legal cooperation in court. Its members are extremely well prepared and qualified, so that Brazil provides an enormous service, of high quality and competence to the foreign Plaintiffs and without any procedural costs. Brazil has not made any reservations regarding the expenses of participation of a lawyer, legal counsel, or regarding the payment of court costs, as provided in article 42, when referring to article 26 of the Convention.

In this respect, it is worth reproducing the provisions of articles 42 and 26 of the Convention:

“Article 42

Any Contracting State may, up to the time of ratification, acceptance, approval or accession, or when making a declaration under Articles 39 or 40, make one or both of the reservations provided for in Articles 24 and 26, third paragraph. No other reservations will be admitted.

Any state may at any time withdraw a reservation it has made. The withdrawal must be notified to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

The effect of the reservation will cease on the first day of the third month after the notification mentioned in the previous paragraph. “

“Article 26

Each Central Authority shall bear the costs resulting from the application of the Convention.

The Central Authority and the other public offices of Contracting States shall not require the payment of costs for the presentation of applications under this Convention. In particular, they may not require the applicant to pay costs and expenses related to the proceedings or, where

applicable, those arising from the participation of a lawyer or legal counsel. However, they may demand payment for the expenses occasioned by the child’s return.

However, any Contracting State may, when making the reservation provided for in Article 42, declare that it shall not be obliged to pay the costs provided for in the preceding paragraph in respect of attendance by counsel or legal advisers or the payment of court costs, unless those costs can be covered by its system of legal and judicial aid.

When ordering the return of the child or regulating access rights within the framework of this Convention, the judicial or administrative authorities may, if necessary, impose on the person who transferred, who retained the child or who prevented the exercise of access rights, the payment of all necessary expenses incurred by or on behalf of the applicant, including travel expenses, expenses incurred in representing the applicant in court and expenses in returning the child, as well as all costs and expenses incurred in locating the child . In the absence of a conventional, bilateral or multilateral measure (such as the Convention), there is another way. This means that when another State, in active or passive requests, is not a signatory to the Convention, and there is no bilateral agreement, diplomatic channels are used. In these cases, the Central Authority is exercised through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Interministerial Ordinance No. 201, of March 21, 2012, regulates the processing of cases that require international legal cooperation. The aforementioned Ordinance, in its Article 1, defines the processing of rogatory letters, as well as requests for direct assistance, active and passive, in civil and criminal matters, in the absence of bilateral or multilateral international cooperation.

As you all know, the proceedings will take place in the Federal Court, since competence is defined by article 109, item III, of the Constitution, when the causes are based on a treaty or contract between the Union and a foreign state or international organization.

1 SILVA, José Affonso da. Comentário Contextual à Constituição. São Paulo: Malheiros, 2005, p. 853.

2. The hearing of children and adolescents as a means to ensure their right to choose and live together

The fundamental point, and in my opinion also determinant, or not, for the return of the child to his or her country of origin or the reestablishment of the right to custody/visitation is related to the hearing of the child by the judge. Every child is guaranteed the fundamental right to live with both parents. To demand that a choice be made between one parent and the other is perhaps the most serious aggression that can be perpetrated against her best interests. It is more than a duty to listen, the child has the right to be heard. Thus, it is worth emphasizing the provisions of Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which, in its Item 1, enshrined that the child shall have the right to their own points of view, as well as the right to express their opinions freely, in accordance with their age. and maturity presented; in Item 2 of the said article, it is provided that the child has the right to be heard in any judicial or administrative proceeding. So, states article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child:

“Article 12

1. States Parties shall ensure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own judgment the right to express his or her views freely in all matters affecting the child, due weight being given to such views, taking into account the age and maturity of the child.

2. For this purpose, the child in particular will be given the opportunity to be heard in any judicial or administrative proceedings affecting it, either directly or by through an

appropriate representative or body, in accordance with the rules procedural of national law.”

The Convention on the Rights of the Child has set age as the limits for the child’s hearing, as well as maturity, without, however, setting a minimum age. In the opposite direction, the ECA has set the minimum age limit of 12 years according to which children should or should not testify in court.

According to Gustavo Ferraz de Campos Monaco, the UN Convention should prevail over the ECA, because the latter “takes the issue concerning maturity to the non-objective level, which was imposed by the age limit of the internal legislation, to favor the psychological and social understanding of the person involved.”5

Children, therefore, should effectively participate in judicial and administrative proceedings, as long as they have a legal interest, that is, as parties, interested third parties, or witnesses, by expressing their opinions regarding the subjective rights that affect them directly or indirectly.

Article 13 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child enshrined that the child shall have the right to freedom of expression, that is, in the words of Solano de Camargo, “freedom of expression and

the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, in oral, written or printed form, in the arts, or through any other media of one’s choice.”6 Article 13 states:

“Article 13

1. The child will have the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the arts, or through any other media of the child’s choice.

2. The exercise of this right may be subject to certain restrictions, which are only those provided by law and considered necessary:

a) for the respect of the rights or reputations of others, or

b) for the protection of national security or public order, or to protect public health and morals.”

We conclude that articles 12 and 13 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child translate their right to freedom of opinion and expression. For José Afonso da Silva the “freedoms of opinion and expression complement and integrate each other, the second consisting in the exteriorization of the first.”7

Thus, guaranteeing for the most interested party, which is the child, the opportunity to have his/her report considered in every judicial or administrative process and without ever requesting a supposed preference as to which parent should live together. The hearing of the child, in case psychological maturity recommends it, must be deliberated with the strict purpose of defining the arrangements for his or her return to the State of habitual residence, as well as, the measures to be provisionally adopted to regulate the coexistence with both parents or guardians, until the cognition of the case by the natural judge becomes viable. In this sense, Pietro Perlingieri teaches us that “the interest of the minor is identified as obtaining personal autonomy and judgment and can also materialize in the possibility of expressing alternative choices and proposals that may be related to the most diverse sectors, from cultural interests to political and affective ones, as long as their psychophysical integrity and the overall growth of their personality are safeguarded.”8

When the Convention refers to maturity, it alludes to the ability to define one’s preferences with an understanding of their possible consequences. The child’s hearing requires respect the norms of due process in judicial proceedings, namely: a) have prior information, expressed in accordance with your age, which allows you to know the situation or matter on which you must express yourself or express your opinion; b) preserve their privacy, which calls for informal hearings, outside the adversarial system, without formalities that could frighten them and without the presence of the parties or their advisors; c) implement the intervention and specialized professionals, when necessary and possible, and according to the child’s age, who know how to properly interpret their expressions. This means that communication with the child may take place in different ways according to his/her evolution or degree of maturity, which will determine the gravitation of the child’s will on the judicial resolution, as stated by Cecilia P. Grossman.9 It is not an easy situation for the judge, because besides covering biological and legal criteria, each child or teenager has an individual degree of maturity, which stems from several factors.

In the process of hearing the child, it is important, for decision-making, to ensure that the child has elements and understands all the information of the judicial exploitation and that he is free to say whether he wants to exercise his right to be heard or not and, also, that it has the freedom to express what information it wants to share or not.

It is clear that the need for the minor to be heard, when his age and maturity allow it, is essential because it is evident that this right to relate to his parents or guardians affects his personal and family sphere, as demonstrated by Silvia Díaz Alabart.10

In Brazil, the hearing of the child has a complementary character and normally occurs from the age of 12, as established by the ECA. In other jurisdictions, such as Spain, for example, children are allowed to be heard from the age of 8, or even earlier if they are mature enough. In Argentina, there is no minimum age as an objective criterion set by law. However, from the age of 13 people acquire broad rights, including the right to be heard in administrative or judicial proceedings. In Chile, there is also no objective legal age criterion for the hearing of children. It is up to the judge to decide whether or not to hear her, whether she is mature enough to be heard. In France, the French Courts admit

hearing between 7 and 9 years old. In Italy, the objective age criterion sets the minimum age limit at 12 years old, as well as children under this age, as long as they are considered capable of understanding, of having “discernment”. In this jurisdiction, it is up to the judge to verify and be convinced that the child’s testimony is contrary to his or her interest or not necessary. The ability of the judge to face the child physically and listen to him, in fact, allows him to know the state in which the child is found, as well as the related dynamics in which he participates and also to verify his positions on the situation in which he finds himself and what life project he formulates for the future, as a result of this hearing, motivating a decision that duly takes into account his will. In Germany, the minimum age for the hearing of a child is 14 years old, with exceptions, as German doctrine and jurisprudence admit that there is consensus for determining the child’s wishes and feelings from the age of 3. For Lohrentz, “the child’s direct contact with the Court is invaluable for the source of information it provides, particularly in matters concerning the person, which at the same time serves as a barometer for obtaining a judicial resolution in accordance with the minor’s interest.”11

In Anglo-Saxon countries, it is no different. In the UK, the minimum age for a child to be heard in court is 4 years. It is worth mentioning that in that jurisdiction the child’s right to be heard is done indirectly, through the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (“Cafcass”), which does not always hear the child. Cafcass is a non-governmental organization created to safeguard and promote the interests of children in family proceedings. Established in 2001, by provision of the Court Services and Criminal Justice Act, Cafcass is accountable to Parliament, currently through the Ministry of Justice. It is an independent body from the Courts, social services, educational and health authorities and other similar bodies. Basically, this body is in charge of looking out for the best interest of the children with their families, and subsequently informs the courts what is considered to be the best interest of the child. In the United States there is no federal law that provides for the hearing of children, it is up to the states to define it, although most states do not have this provision, and it is up to the judge to decide whether or not the hearing is appropriate. There are cases of 8- and 9-year-old children who have been heard. However, I reiterate that the important thing is to provide the opportunity to hear the child in any judicial or administrative hearing process. So much so that Article 20 of the Convention states that:

“Article 20

The return of the child in accordance with the provisions contained in Article 12 may be refused where it is not compatible with the fundamental principles of the requested State regarding the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

It can be noted, therefore, that the reports can also be a defense argument for the non-return to the country of habitual residence and, in this case, it is necessary even for the child to eventually express his or her objection to the return, as Carolina Marin Pedreño teaches us:

“Siendo el objeto del Convenio asegurar la pronta restituición del menor, cuando este haya alcanzado una edad y grado de madurez suficiente, es decir, que aconsejen tener en cuenta su opinión, and provided that the defense has been built on this, the judge may, according to his discretion, decide on the convenience or not of return, and, consequently, condemn him or not.

En este orden de cosas, conviene que sepamos que puede objetarse el retorno a un país determinado, pero no a un cuidador en particular, no estabelecendo el Convenio una edad mínima del menor para que su opinión (objeción) pueda ser tenida en cuenta.”12

This situation is foreseen in article 13 of the Convention, which provides for the possibility of objecting to the child’s return to his or her country of habitual residence, provided the child has reached an age and degree of maturity that would allow his or her views on the matter to be taken into consideration.

In the same sense, as stated by Glícia Brazil: “The right to be heard cannot be confused with the duty to speak, generated by moral coercion”. Sometimes, when suffering moral violence, “to respect the child’s speech is to order him to shut up.13

The Convention does not provide for justifications by children based, for example, on issues such as school adjustment or other arguments referring to their alleged well-being. The objection must deal with relevant issues, such as parental alienation, continuous physical, psychological or sexual abuse, committed by their guardians or parents who have remained in their place of habitual residence.

In these opportunities, when there is no agreement, it will be up to the Central Authority to request the judge to allow the child to speak and the judge, armed with information about the situation of that specific case, has the power to deliberate, according to the best interests of the child. But, caution is needed so that there is no confusion with the desire of the vulnerable, considering that there is not always enough maturity to decide, as Rolf Madaleno states: “All that the judge cannot do is to confuse the good of the minor with the desire of the minor, because his will is not always mature enough to decide for what really suits him.”14 Of course, it is not a matter of unconditional acceptance of the child’s wishes, which could even be detrimental to the child’s education and real interests. His word is not binding and must be evaluated with the other elements of the judgment. But the child should always have the opportunity to be heard, if his age and maturity allow it. From this point on, the work of professional court assistants, such as psychologists, makes all the difference and should be called upon. It is also recommended that the hearing be held in a neutral environment to avoid any kind of trauma, in accordance with the rules of procedure of the national legislation, as well as, by means of a technically trained professional, to comply with the standards in the production of psychological expertise.

2 DOLINGER, Jacob. A família no direito internacional privado. A família no direito internacional privado. In: DOLINGER, Jacob Direito civil internacional, v.I, t. segundo, parte especial. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 2003, p. 242.

3 PEREIRA, Rodrigo da Cunha. Divórcio: teoria e prática. 4ª ed. de acordo com a Emenda Constitucional n . 66/2010. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2013, p. 90.

4 FACHIN, Luiz Edson. Questões do direito civil brasileiro contemporâneo. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 2008, p. 116.

5 MONACO, Gustavo Ferraz de Campos. Direitos da criança e a adoção internacional. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais, 2002, p. 74.

6 CAMARGO, Solano de. O Direito da criança ser ouvida – aspectos internacionais. Famílias Internacionais: seus Direitos, seus Deveres / Hughes Fulchir; Gustavo Ferraz de Campos Monaco (organizers). São Paulo: Intelecto Editora, 2016, p. 256.

7 SILVA, José Affonso da. Direitos Humanos da Criança. Revista Trimestral de Direito Público. São Paulo: Malheiros, 1997, 9.10

8 PERLINGIERI, Pietro. Perfis do direito civil; tradução de: Maria Cristina De Cicco. 3.ed., rev. e ampl.. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 2002, pp. 259-260.

9 GROSSMANN, Cecilia P. Nuevos perfiles del derecho de familia/ coordinado por Aída Kemelmajer de Carlucci y Leonardo B. Pérez Gallardo. 1st edition. Santa Fe: Rubinzal-Culzoni, 2006, pp. 208 – 209.

10 ALABART, Silvia Diaz. Nuevos perfiles del derecho de familia/ coordinado por Aída Kemelmajer de Carlucci y Leonardo B. Pérez Gallardo. 1st edition. Santa Fe: Rubinzal-Culzoni, 2006, p. 388.

11 LOHRENTZ, U. “Anhang II Verfahrensgrundsätze,” in Handbuch Anwalt des Kindes, verfahrensbeisstandschaft und Umgangspfelegeschaft für Kinder und Judendliche (w, Rochling editor), Nomos Praxis, 2009, p. 282.

Conclusions

An analogy can be made between the Convention and the “picture of a landscape”. The child is not a party directly, but is the protagonist of this landscape, whose outcome of the application of the Convention affects him/her and makes him/her the main figure. The contracting states, authorities and parties involved have to work within the boundaries of this framework, they cannot go beyond the limits of the frame of this framework. The rite is specific, the response must be quick.

Therefore, the ordinary rules of the normal course of proceedings do not apply in such cases. For example, psychologists should not be heard, because it would take an excessive amount of time for the decision, unless the judge understands that the complexity of the case warrants it, and orders that the child be heard with the assistance of professionals, on an exceptional basis, in a short period of time, even though this possibility is not provided for in the Convention.

Therefore, it is worth remembering that not even the practice of hearing the child foreseen in Law 13.431/17, article 8, the so-called “Special Testimony” should be observed, since this measure will be up to the natural court – “Art. 8 Special Testimony is the procedure of hearing a child or adolescent victim or witness of violence before a police or judicial authority”.

However, reality has shown that the majority of Brazilian judges understand that the common rite should be applied to international child abduction cases when they are heard by the Judiciary, but, in fact, it is not correct to do so, since this is not what is foreseen in the Convention. Although the Convention does not set a minimum age for the child to be heard, all the provisions therein are listed for his or her benefit. Therefore, it is necessary to respect the Convention, in all its terms, extracting from it the best result for its effectiveness, which is to fulfill the request quickly and respect the transfer or return of the child to their country of habitual residence or that their coexistence or visitation rights are observed and preserved. Therefore, it is reiterated, the applicability that has to be fast, as mentioned, and must also be appreciated as a systemic interpretation, that is, the Convention applies, together with the other norms of international scope, among them the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which stipulates that children must be heard whenever their age and maturity situation permits. It is up to the judge, as the interpreter of the law and enforcer of justice to do so, so that he has all the necessary elements available for his best conviction. Only then will this “picture of a landscape” be fully appreciated and fulfilled, allowing the child the best outcome for the concrete situation.

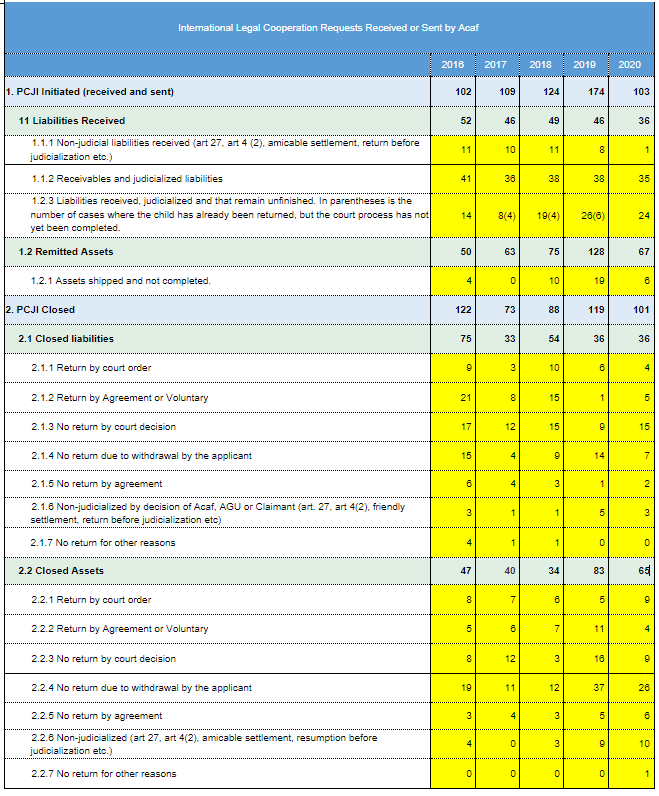

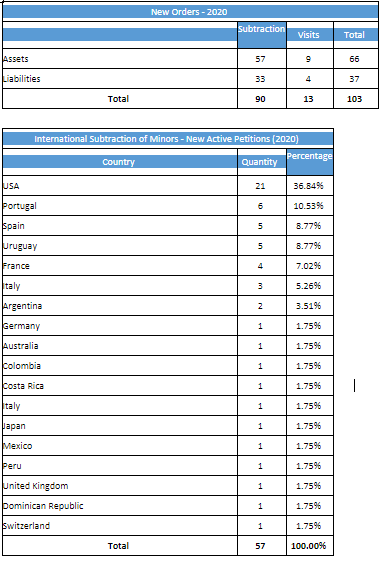

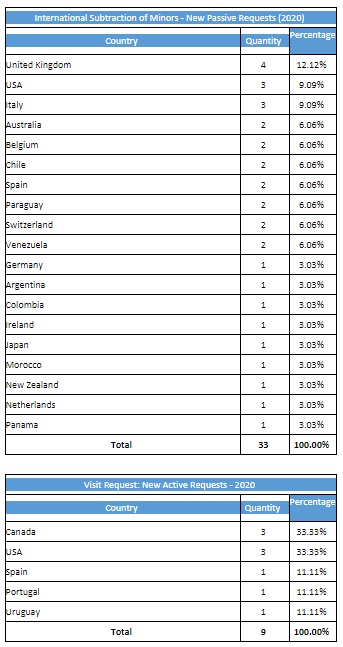

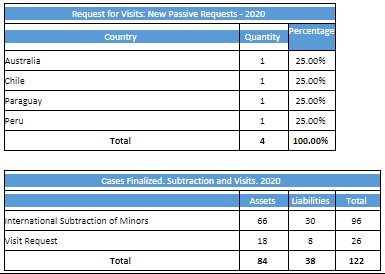

According to data from the Federal Central Administrative Authority for Adoption and International Abduction of Children and Adolescents (ACAF),15 restricted to cases in which it was demanded, in 2020 alone – the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic – 103 cases were registered (66 active and 37 passive), including subtraction and visits. Among this total, 90 cases of subtraction were reported (57 active and 33 passive), that is, Brazil demanded more as a requesting country. Regarding the request for views, there were 13 cases (9 active and 4 passive). In the same year, 122 incidents were also completed: 96 subtraction incidents (66 active and 30 passive) and 26 visit request incidents (18 active and 8 passive).

Between 2016 and 2019, there were 509 cases initiated (2016: 102/ 2017: 109/ 2018: 124 and 2019: 174), an average of just over 127 per year. However, it is important to note that in almost every year the active cases outnumbered the liabilities, except in 2016. Regarding those closed between 2016 and 2020, there were 402 (2016: 122/ 2017: 73/2018: 88 and 2019: 119), presenting on average 100 cases per year, lower than 2020. All these data, as well as more detailed information, including which are the most demanding jurisdictions, as well as those that are most demanded in international child abduction cases, are described in Annex I to this article (ANNEX I).

Interestingly, in passive cases that occurred in the mentioned periods, with the exception of 2019, most were closed by agreement or voluntary act, to the detriment of a court decision. All these numbers also show that situations regarding international child abduction are significantly low, considering that the Judiciary counted, in 2019, among the

most demanded subjects in the first degree of jurisdiction: 1,135,599 cases (3.79% of the total of cases), in the area of Civil Law – Family/Food, according to the report “Justice in Numbers 2020”16, of the National Council of Justice (CNJ).

In view of all the data and information presented in this article, it is possible to affirm that the legal provision exists, since Brazil ratified and adhered to the Convention on the Rights of the Child. And it is obvious that we need to respect and comply with these rules also to make it clear to the world that the country aims at the best interest of the child. But care is needed, because most of the time the child’s voice – whether it is someone who is in childhood or adolescence – does not receive due importance so that the judge can fully constitute his conviction and make the best decision for the future of a human being still in the formation phase and who deserves a promising future, in the achievement of the healthy development of his personality, as well as in the search for his integral happiness.

12 MARÍN PEDREÑO, Carolina. Sustracción Internacional de Menores. Málaga: Editorial Ley 57, 2015, p. 60 – 61.

13 BRAZIL, Glícia Barbosa de Mattos. In Famílias e sucessões: polêmicas, tendências e inovações / coordinated por Rodrigo da Cunha Pereira and Maria Berenice Dias. Belo Horizonte: IBDFAM, 2018, p. 517.

14 MADALENO, Rolf, Curso de direito de família. 4ª edição. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2011, p. 324.

ANNEX I – Requests for International Legal Cooperation received or sent by the Federal Administrative Central Authority for the International Adoption and Abduction of Children and Adolescents, from the Department of Asset Recovery and International Legal Cooperation, Ministry of Justice and Public Security (ACAF/DRCI/MJSP) from 2016 to 2020

Note 1: Data provided by the Central Federal Administrative Authority for Adoption and International Abduction of Children and Adolescents, of the Department of Asset Recovery and International Legal Cooperation, Ministry of Justice and Public Security (ACAF/DRCI/MJSP).

Note 2: The data do not include all cases related to the 1980 Hague Convention, but only those detected by ACAF, and may contain differences in classification in terms of typology.

Note 3: Prior to 2016 there was no official compilation by the Brazilian Central Authority on the topic.

Detailing 2015-2020:

Breakdown 2020 by country:

Bibliography

ALABART, Silvia Diaz. Nuevos pefiles del derecho de familia/ coordinado por Aída Kemelmajer de Carlucci y Leonardo B. Pérez Gallardo. 1st edition. Santa Fe: Rubinzal-Culzoni, p. 363-388, 2006.

BRAZIL, Glícia Barbosa de Mattos. In Famílias e sucessões: polêmicas, tendências e inovações / coordinated by Rodrigo da Cunha Pereira and Maria Berenice Dias. Belo Horizonte: IBDFAM, p. 503 – 518, 2018.

CAMARGO, Solano de. O Direito da criança ser ouvida – aspectos internacionais. Famílias Internacionais: seus Direitos, seus Deveres / Hughes Fulchir; Gustavo Ferraz de Campos Monaco (organizers). São Paulo: Intelecto Editora, 2016.

DINIZ, Maria Helena. O estado atual do biodireito. 3 ed. increased and updated. According to the new Civil Code (Law n. 10.406/2002) and Law n. 11.105/2005. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2006.

DOLINGER, Jacob. A criança no direito internacional. In: DOLINGER, Jacob. Tratado de Direito Internacional Privado, v.1, t. 2, parte especial. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 2003.

FACHIN, Luiz Edson. A nova filiação – Crise e superação do estabelecimento da paternidade. Repensando o direito de família, Anais do I Congresso Brasileiro de Direito de Família. Belo Horizonte: Del Rey, p. 123-133, 1999.

FACHIN, Luiz Edson. Questões do direito civil brasileiro contemporâneo. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 2008.

GRISARD FILHO, Waldyr. Guarda compartilhada: um novo modelo de responsabilidade parental. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais, 2002.

GROSSMANN, Cecilia P. Nuevos perfiles del derecho de familia/ coordinado por Aída Kemelmajer de Carlucci y Leonardo B. Pérez Gallardo. 1st edition. Santa Fe: Rubinzal-Culzoni, p. 179-214, 2006.

LAFER, Celso. A reconstrução dos direitos humanos. A dialogue with Hannah Arendt’s thought. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1998.

LOHRENTZ, U. “Anhang II Verfahrensgrundsätze,” in Handbuch Anwalt des Kindes, verfahrensbeisstandschaft und Umgangspfelegeschaft für Kinder und Judendliche (w, Rochling editor), Nomos Praxis, 2009.

LÔBO, Paulo Luiz Netto. Entidades familiares constitucionalizadas: para além do numerus clausus. Brazilian Journal of Family Law. Porto Alegre, n. 12, p. 40-45, 2002.

MADALENO, Rolf, Curso de direito de família. 4ª edição. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2011.

MARÍN PEDREÑO, Carolina. Sustracción Internacional de Menores. Málaga: Editorial Ley 57, 2015.

MONACO, Gustavo Ferraz de Campos. Direitos da criança e a adoção internacional. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais, 2002.

PEREIRA, Rodrigo da Cunha. Divórcio: teoria e prática. 4th ed. according to Constitutional Amendment n. 66/2010. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2013.

PERLINGIERI, Pietro. Perfis do direito civil; tradução de: Maria Cristina De Cicco. 3.ed., rev. e ampl. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 2002.

PIOVESAN, Flávia. Direitos humanos e o Direito Constitucional Internacional. 4. ed. São Paulo: Max Limonad, 2000.

SILVA, José Affonso da. Comentário Contextual à Constituição. São Paulo: Malheiros, 2005.

SILVA, José Affonso da. Direitos Humanos da Criança. Revista Trimestral de Direito Público. São Paulo: Malheiros, 1997.

SILVA PEREIRA, Tânia da. O Princípio do melhor interesse da criança: da teoria à prática. A família na travessia do milênio, Anais do II congresso Brasileiro de Direito da Família. Belo Horizonte: Del Rey, p. 215-234, 2000.